Self Portraits (Medicalised) At Age

Twenty-Six

Through

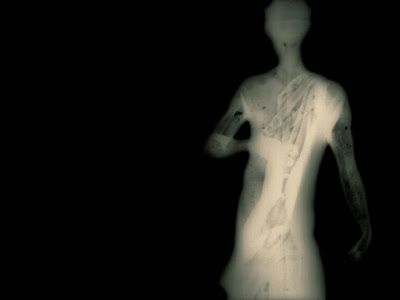

portraiture, drawing and digital media, Self

Portraits (Medicalised) At Age Twenty-Six investigates medicalised-imaging

and images of the self as an enquiry into the seen and unseen aspects of the

human body. By disrupting tropes of Renaissance portraiture and associated

conventions, this series imitates classic poses from self-portraits to question

notions of the classic beauty and the contemporary digital portrait. Through the

introduction of medical imaging upon these images, it also poses an enquiry

into medical interventions upon the human body and the indistinct medicalised imprint

that is created from these interventions.

Self Portraits (Medicalised) At Age

Twenty-Six is a series of

six layered works that sit upon light boxes. By appropriating the poses seen

within the self-portraits of Albrecht Durer, four photographs were created as

base layers. Layered upon these portraits are collages of medical imaging combined

with hand and digital drawing. This re-invention of the image is a means to find new pathways to discuss

the effects of medicalisation.

The

portraits I have appropriated are from various stages of Durer’s life and the title

of this series is a response to Durer’s work, copying the layout of his

self-portrait titles. Durer depicts certain poses that uphold the classical

ideals of portraiture from the Renaissance. By mimicking these poses I seek to

follow in his footsteps, constructing my image as someone worthy of being

represented in a portrait. In each of these portraits Durer is dressed

opulently, his hair a prominent feature. Careful planning went into each aspect

of his portraits and through my costuming I attempt something similar. The

green outfit is representative of a medical gown, similar to the ones worn into

surgery, while the other poses are my usual clothing but presented in a

classical way. Durer’s hair is a key feature of his character and, as I closely

associate my hair with my own identity, I have accentuated the bright purple in

it.

These

self-portraits explore my lived experience, investigating the effects of

medicalisation upon the human body and identity. Societal stigmas surrounding

mental and chronic illness are still prevalent today. In considering that is

easy to doubt issues that cannot be seen, to question their existence, and chronical

illness is often disregarded.

Presented

in a series, on top of light boxes, each self-portrait is a layered work. This brings

our visual attention to the invisible illness by revealing the medical imaging

of x-rays and ultrasounds through photographic portraits. David Maisel x-rays

historical art objects in his own practice states that:

“The x-ray has historically been used for the

structural examination of art and artefacts much as physicians examine bones

and internal organs; it reveals losses, replacements, methods of construction,

and internal trauma that may not be visible to the naked eye.”

In

considering my personal illnesses as invisible, the ‘internal trauma’ is

hidden, however, the external, physical effects are visible. The use of medical

imaging documents illnesses as a ‘construction’ of the real. It records the

truth of our bodies and exists as evidence as validation of lived experience.

Through the collision of digital drawing, collage and the mimicked classical

portraits, I reference the clinical aspect of medical imaging and the

beginnings of my own personal experience of medicalisation as a young woman.

The white light behind the image makes viewing layers possible, enabling us to

see what lies beneath the surface.

In Reach

(2000) and Trap - self portrait (1998) Justine Cooper

explores medical imaging and her own translation of the self through this

technology. She had MRI scans taken of different parts of her body and explores

a restructuring of her body through this technology. Cooper writes:

“At the point of imaging, solid organic tissue

is transposed into an ephemeral digital language of zeroes and ones, in much

the same way that a cipher uses substitution to encrypt information. In the

resulting physical work I attempt to retain some of the ephemerality of that

earlier translation into digital space, some of the obscurity of the cipher,

while offsetting them against the apparent tangibility of the body. Instead of

a simple dichotomy between invisible and apparent, virtual and physical,

continuity and displacement, an attempt at a less distinct or concrete

disclosure is being made where the gap becomes the viewer's space.”

Medical

imaging creates a digital language through which the body is understood and through

the digital collaging of my own scans, a ghostly, figurative image of my

physical body is created. It is an echo of the original image, a ghostly

dismembered body that forms a self-portrait in a new language. The scanned

collages continue to inform the original portrait and the portrait continues to

update the scans and thus a feedback loop is generated with each system of

seeing and understanding the body, informing the other.

This

series proposes that what is seen on the surface is not always representative

of the truth and it invites the viewer to look beyond the surface of the skin.

There can be a true disconnect between our physical body and our own sense of

self. By rupturing and designing images

through collage using medical imaging, photography and hand and digital drawing

this enquiry is realised.